Marie Curie's Radiant Legacy— the woman who lit up science

- mannkarissa

- Nov 15, 2025

- 4 min read

This November, as we're cleaning up from Halloween and preparing for Thanksgiving, we should take a moment to recognize the 158th birthday of a woman who set the foundation for decades of immaculate science and inspired the world.

Marie Curie, born Maria Skłodowska on November 7th, 1867, in Warsaw, Russia (now Poland), was the last of five children to her parents, Wladisaw and Bronislava. They were teachers who passed down their passion for learning onto their children but struggled financially after Marie's mother died. Accordingly, to contribute an income, Marie took a job as a governess (tutor), where her love for learning and eager curiosity blossomed. In 1891, she began attending Sorbonne University in France, where she earned her degrees in physics and mathematics, an opportunity not commonly offered to women in Russia at the time.

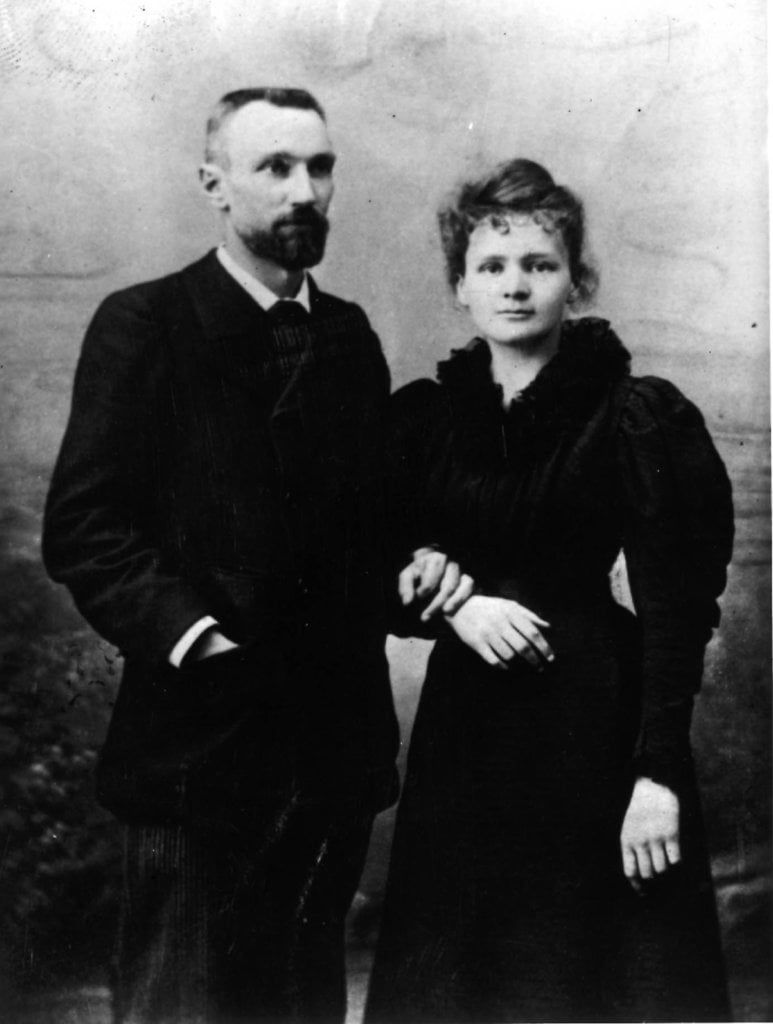

Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre Curie

In 1894, Marie married her husband, Pierre Curie, who was also a scientist, and the pair got to work. They became researchers at the School of Chemistry and Physics in Paris, France, and investigated the newly discovered phenomenon of invisible rays excreted by uranium penetrating solid matter, fog, and film. It was at this occupation that Curie uncovered a new chemical element. While examining samples of pitchblende, a mineral containing uranium ore, she realized the sample she was studying was significantly more radioactive than pure uranium. She soon concluded that the amount of radiation she was detecting could not be caused by the uranium alone— another element had to be responsible.

Though, other scientists had their doubts. Curie was unable to produce an isolated, physical sample of the new compound because its existence was only implied by the unusual radioactivity of the pitchblende. This only further fueled her persistence. Curie and her husband dissolved the pitchblende in acid to separate the elements inside. What resulted was a fine, black powder 330 times more radioactive than uranium: polonium, atomic number 84.

Still, her curiosity grew. Further research uncovered a residue left behind after extracting polonium that was even more radioactive: radium, which Curie was finally able to produce an isolated sample of in 1902. In 1903, Curie, her husband, and co-scientist Henri Becquerel earned a Nobel Peace Prize in Physics for their remarkable work.

While Curie's knowledge on radioactivity was significant, it missed one vital aspect— the lethal ailment of radiation sickness.

Curie and her fellow researchers began to feel mysteriously sick during their experiments with the radioactive elements, even working with open sores in their hands from frequent handling of the material. Today, we can credit these symptoms to acute radiation poisoning, but it's difficult to know if Curie ever suspected the hazardousness of her work.

Radiation sickness occurs when energy released from atoms in the form of radiation enters the body and damages cells, specifically DNA, which is the vital genetic code responsible for commanding important functions in the cell. Depending on the dose received, radiation sickness can cause nausea, headache, fever, hair loss, weakness, bloody vomit, burns, fatigue, cancer, and, in severe cases, death. Curie and her peers were exposed to this threat through the highly radioactive elements of uranium, polonium, and radium they worked with.

Despite the toll her work took on her health, Curie earned her second Nobel Peace Prize in 1911 in Chemistry for creating a method to measure radioactivity. The same year, she became director for a laboratory in Sorbonne's first radium institute and the Red Cross Radiological Service, where she toured Paris to collect old technology to transform into small x-ray units that could be used on the battlefield of World War One. Curie and her daughter, Irene, used these machines at casualty clearings to x-ray wounded men, allowing doctors to observe motion inside their bodies.

Marie Curie and her daughter, Irene

After decades of innovative, ingenious work, Marie Curie died on July 4th, 1934, at age 66 from aplastic pernicious anemia— a condition attributed to her long-term exposure to radiation.

After a magnificent life of tireless research that earned her several awards, including Nobel Peace Prizes, the Ellan Richard's Research Prize, the Grand Prix du Marquis d'Argenteuil Award, Edinburgh University's Cameron Prize, and several honorary degrees, Curie left behind two daughters. Her eldest child, Irene, went on to be a radiation scientist as well, earning a Nobel Peace Prize of her own for creating artificial radiation. Radiation eventually took her life, too, in the form of leukemia in 1956.

Marie Curie indefinitely exists as a symbol of scholarship and perseverance for women around the world. Despite great adversity and doubt, she became one of the most revered scientists, and her foundational discoveries still benefit us today. Most of all, she contributed the enormous sacrifice of her life in the name of curiosity, a feature of hers that still lingers 158 years later. In her words, one of the most important lessons we can derive from her legacy is that "nothing in life is to be feared; it is only to be understood."

Sources:

Comments